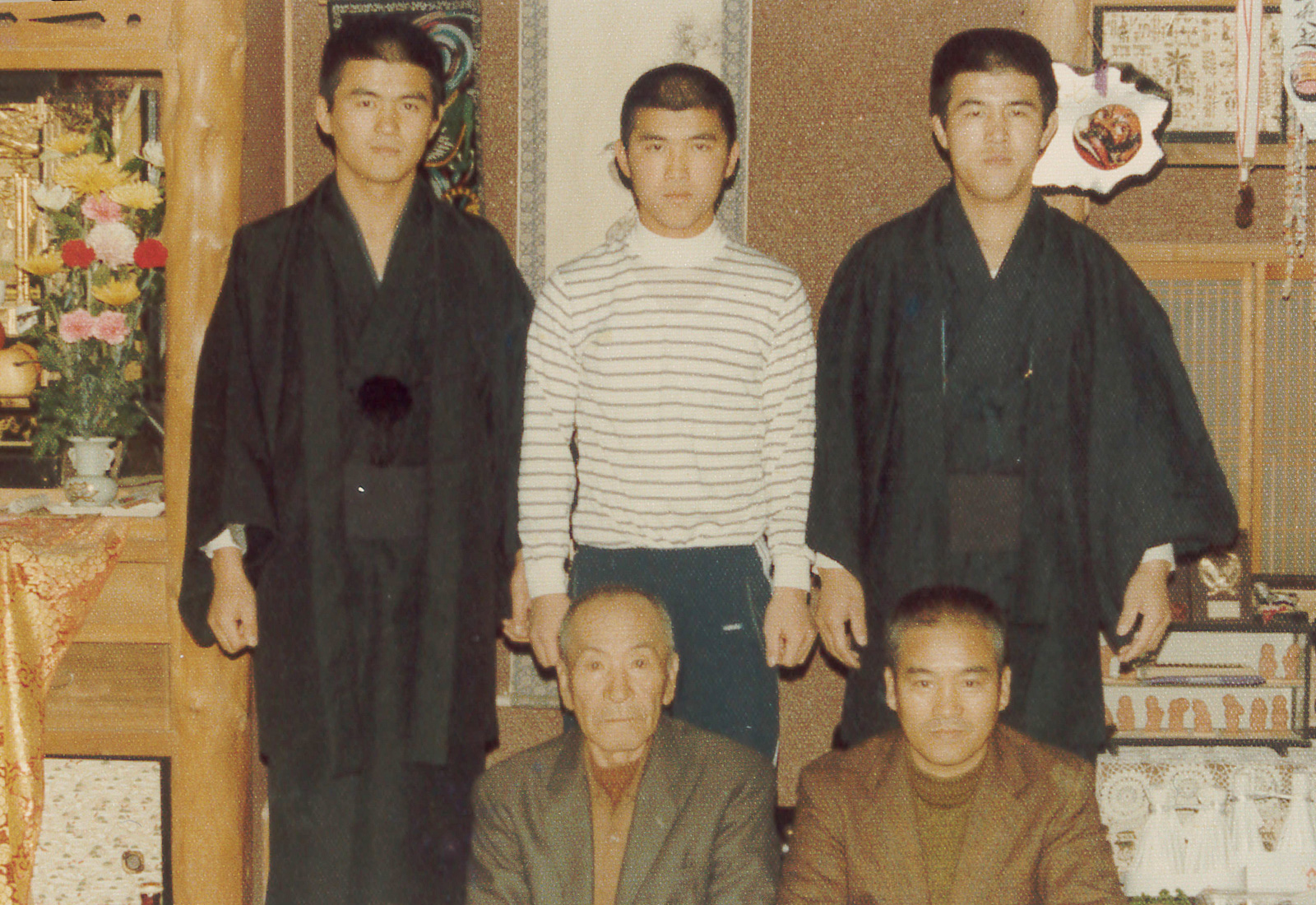

became the dream of his sons,

and their dream

became the hope of Japanese agriculture.

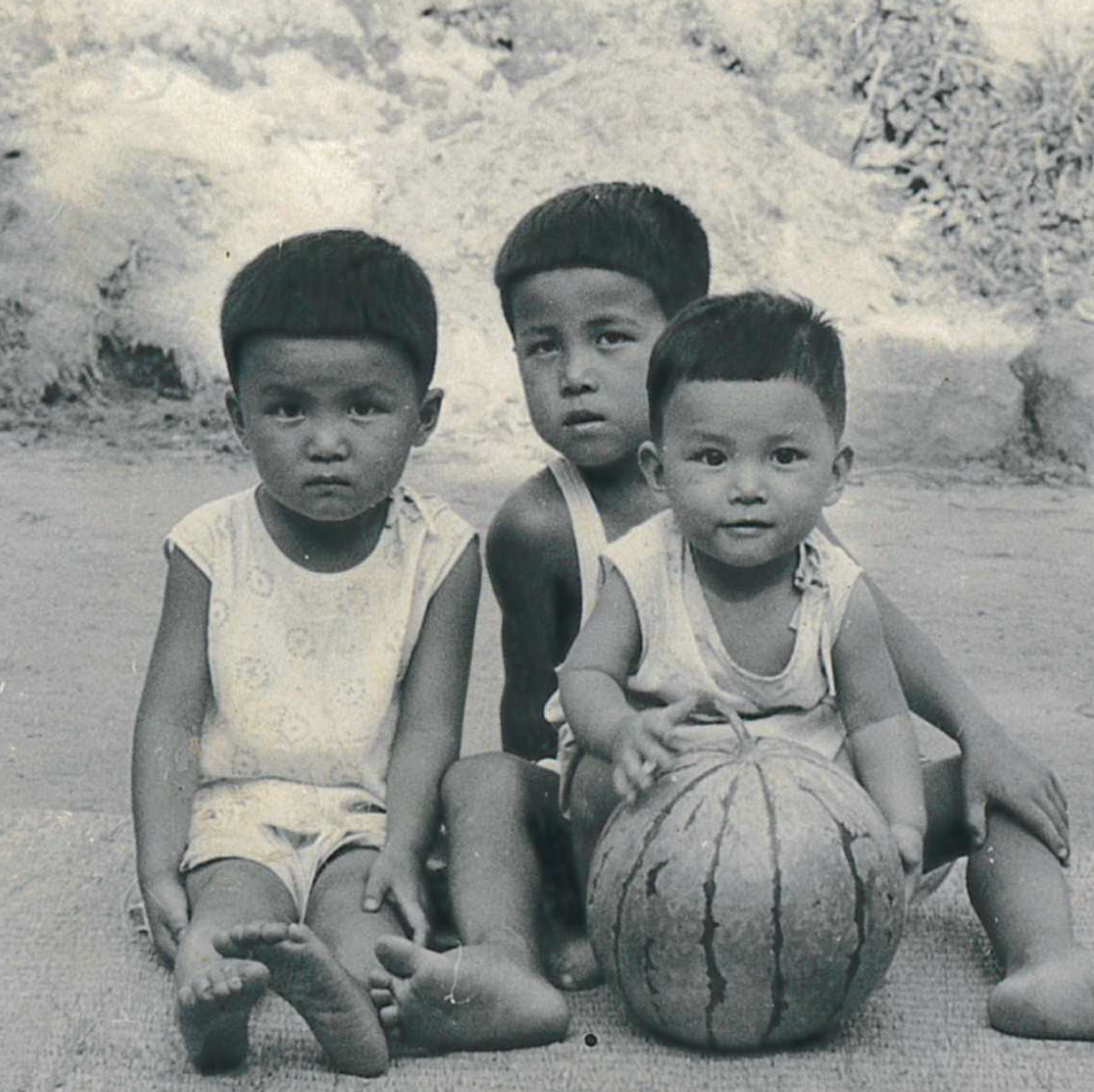

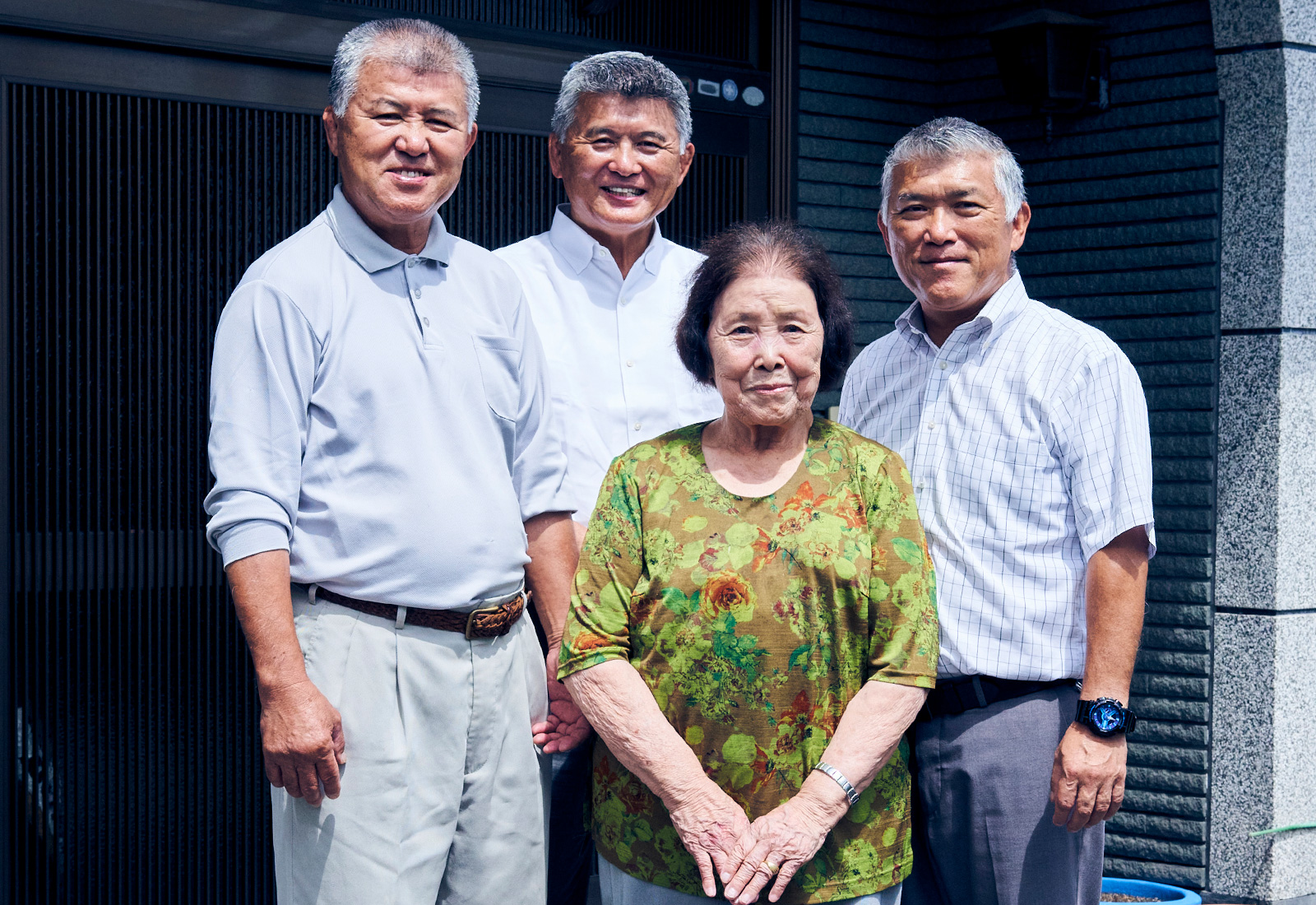

Ichiro KamimuraPresident and CEO,

Kamimura Livestock Co., Ltd.

Masashi KamimuraPresident and CEO,

Kamichiku Holdings Co., Ltd.

Hiroyuki KamimuraExecutive Managing Director,

Kamichiku Co., Ltd.

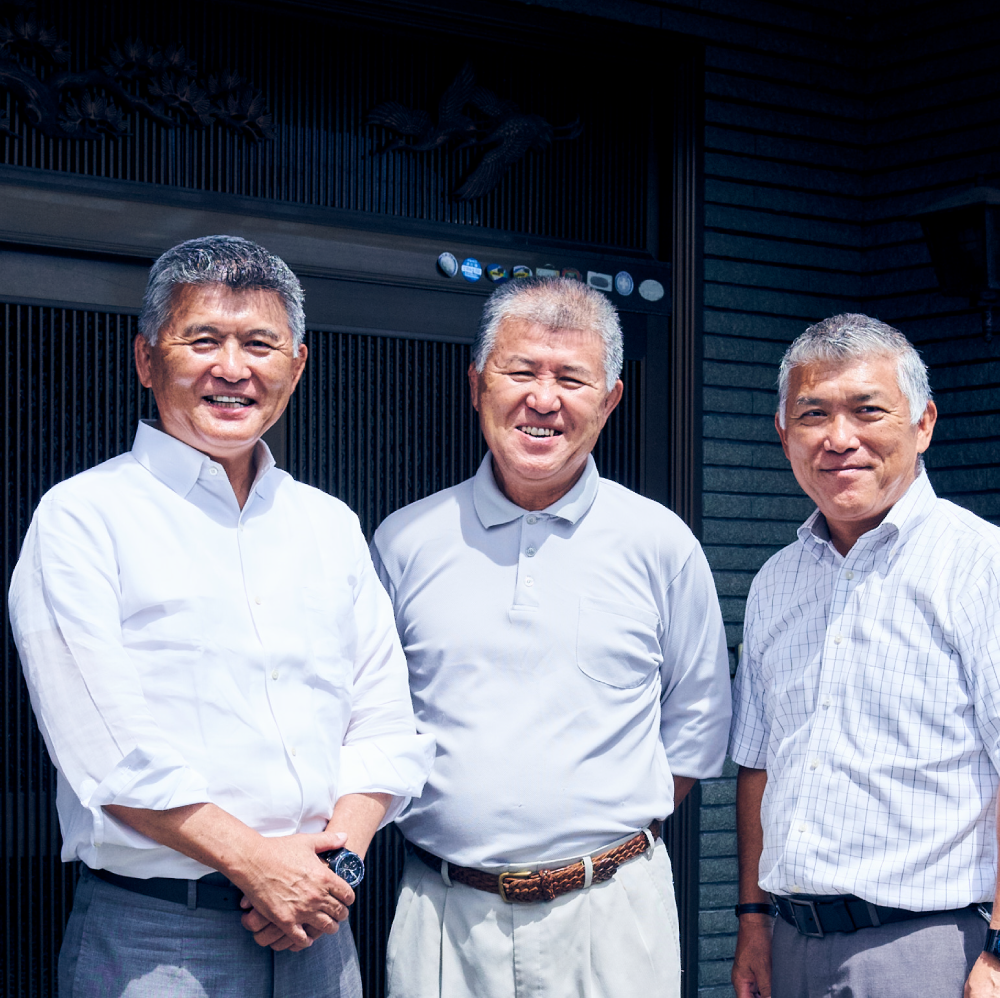

A Challenge Born from the Bond of Three Brothers and a Father's Vision

The founding of the Kamichiku Group marks more than the launch of a business

—it reflects a journey of determination, built on the strong partnership of three brothers

and guided by their father’s firm belief in a shared purpose.

From the outset, the company was driven by a clear and forward-looking vision.

he father of Kamichiku Group’s founder, Masashi Kamimura, envisioned more than simply passing down the family farm—he continually asked himself: How can agriculture truly survive? In an industry where production, processing, and sales are typically divided among separate entities, he grew increasingly frustrated that the value of the cattle he raised was being determined by others.

From this experience, he became convinced that the sustainability of agriculture depended on a fully integrated model—one that managed every step, from production through to sales, within a single organization. Inspired by this vision, he assigned each stage of the value chain to one of his three sons, including Masashi Kamimura, laying the foundation for a new kind of agricultural enterprise.

This marked the beginning of a bold challenge to industry norms. By overseeing everything from livestock production to processing, distribution, and retail, the Kamimura family created a vertically integrated system that delivered new and enduring value to the world of agriculture.

Their father, Toiichi, often spoke to his three sons about both the beauty and the hardships of agriculture.

The eldest son, Ichiro, laid the groundwork as a livestock farmer. The second son, Masashi, took responsibility for meat processing and wholesale, while the youngest son, Hiroyuki, managed retail and the food service operations. Together, they built an integrated system designed to bring the appeal of high-quality meat products directly to consumers.

This collaboration across distinct roles was a pivotal step in bringing their father’s vision to life—creating an agricultural model that bridges producers and consumers. Each brother followed his own path but remained united by a strong family bond, supporting one another as they expanded the business.

Their father’s concept of the “six-faceted integration model for agriculture” went beyond simply dividing responsibilities. It was grounded in the belief that by seamlessly integrating feed production, livestock farming, meat processing, distribution, and food service, they could generate greater value. This integrated approach became the engine driving the remarkable growth of their enterprise.

Challenges and Growth

The growth of the Kamichiku Group was never without hardship. They faced periods of tight cash flow and setbacks that tested their resolve. Working with living animals meant encountering unforeseen challenges repeatedly, yet each obstacle was met head-on and overcome—with the steadfast support of partners and customers—strengthening the company along the way. Throughout it all, the three brothers remained committed to their individual roles, relentlessly advancing toward their father’s vision.

Over time, the Kamichiku Group began to spark a new momentum within the livestock industry, setting a fresh standard for integrated agricultural innovation.

Together with our sunflower-like mother.

The Six-Faceted Integration Model Built Through the Brothers’ Cooperation

The strength of the Kamichiku Group lies in its unique six-faceted integration model, which unifies all stages of the value chain—from primary to tertiary industries. By managing every process in-house—from cattle breeding and rearing to meat processing, distribution, and direct delivery to consumers—the Group has established a business model unlike any other. This integration has even expanded to include feed production, generating additional value and reinforcing self-sufficiency.

This comprehensive approach allows the Kamichiku Group to maintain full control over product quality, develop offerings that reflect consumer needs, and strengthen its competitive advantage. Rooted in the cooperation of the three brothers, the six-faceted integration model continues to drive sustainable growth and innovation across the entire agricultural supply chain.

Looking to the Future

The Kamichiku Group’s vision extends beyond agricultural management—it is rooted in revitalizing local communities and making a lasting contribution to society.

Today, the Group operates both in Japan and internationally, proudly delivering Japan’s exceptional Wagyu beef to customers around the world.

As it continues to grow, the Kamichiku Group remains committed to shaping the future of the global agricultural and livestock industries. What began as a shared dream among three brothers has become a driving force behind the Group’s evolution—and that spirit will live on through the next generation.